The Photograph 1977

Actually did it improve as it went on or did I just learn how to endure it? The piece turned out to be a sneer at arts journalism and the elitism of media types in the big smoke, with a good slosh of the bucolic Gothic mode of Robin Red Breast thrown in, to bring the snark alive. That ought to be enough to say about something so minor, but, since I sat through the whole thing I might as well put down a blow-by-blow account for anyone else who feels mildly curious after having watched ten minutes of the play, but not curious enough to actually want to waste one and a half hours of their life in sitting it out, as I did, regrettably.

So here goes.

After the initial puzzling vignette, the play opens to a view of the front hall of what looks to be a recently-built (for the time) house. In the hall, we see a moderately built, clean shaven man in a towelling dressing-gown picking up the morning’s post and shuffling through the envelopes he finds on the door mat, while he talks to his wife, who is still in bed (out of shot). The man, who looks a bit like Des O'Connor, (insofar as I remember what Des O'Connor looks like), goes into the kitchen and puts breakfast things on a tray. The couple continue to talk from room to room in what felt to me to be a very stilted way. Perhaps it is the script that is flawed and creates the impression that the dialogue just doesn’t work. Or perhaps it is the directing - are all scripts only as good as the performances that directors can persuade actors to produce?

In any case, the actor who plays the husband seems mannered to me at this point - and possibly throughout; like a smell, eventually one begins to not notice a bad performance, which to start with seems unignorable. Certainly in these first scenes the actor fails to disguise the fact that the script is loaded almost entirely with exposition. Which of course is useful, as we learn that this man is called Michael and he is a bit of a celeb, some kind of journalist with a column and a role at the BBC. His wife, called Jill, is nervy. They certainly appear to get on each other's nerves. Michael tells Jill not to slop her coffee, Jill tells Michael he’d better eat his muesli, Michael talks about his fans, Jill scoffs.

Eventually Michael notices that among the bills and circulars arriving in the morning's post is a handwritten envelope. He opens it at the urging of Jill and finds it contains a black and white photograph of two very young people sitting in front of a caravan. A tense conversation ensues about who it might be, leading Jill to ask, “Have you been up to something”. Michael says he hasn’t, with the slight unspoken implication of, “at least not lately”. Jill springs out of bed, announcing she’s getting up, and rushes out of the room. Michael says, “Oh Jill, don’t get into one of your loony states.”

At this point, neither character has exhibited any trait that might make me care about them, and I find myself continuing not to care much about them as the scene switches to the kitchen on Sunday evening, two days later. The couple are discovered listening to the radio, on which Michael can be heard, giving a lecture of a vaguely philosophical nature. When it finishes, Jill begins to speak, She thinks she’s found out where the caravan is that is visible in the photograph that arrived that morning. Michael protests that the entire weekend has been taken up with “that bloody photograph”. He rather unwisely goes on to say he couldn’t care less who “two lumpy teenage working class girls” are. Jill tells him he's always had “an itch for the working classes”. When he denies this she asks, if he doesn't have this itch, why did he marry her. He turns to her and roars, “I married you because you were pregnant - and then you lost the sodding child”. Jill leaves the room, (again). Michael calls out to her, asking her why she provokes him and claiming that he wouldn’t snap, if she didn’t provoke. He apologises wearily, adding “I know your ill, and I try to remember.” She says she’s been through his appointment book and can see he’s recently been in the same area as that from which the photograph was sent.

The scene cuts to Jill consulting a counsellor or psychiatrist. She complains of panic and explains how she and her husband met, (he was giving a talk at the teachers college she was attending and one thing led to another). She talks about how inadequate she feels in her husband’s world and bursts out that she can only keep her hold on him by being helpless. She cries copiously.

In the next scene, we are introduced to Michael lying in bed with someone, somewhere. The camera is fixed on Michael's face. He says he can’t leave Jill as she has no family and is ill. He admits she should leave him and that he thinks he destroys people. The person he’s in bed with does not speak, nor do we see anything of them except their forearms. On one wrist there is a gold bracelet and on the other a tattoo. I think in the 1970s the tattoo signalled that Michael is in bed with a man.

And now, at last, things brighten up - the English rural Gothic heaves into view. We move to the interior of a caravan. Yes, a caravan, perhaps that caravan, the one in the photograph, oooooh. A David Cassidy lookalike is sitting in the foreground of the caravan's interior, holding a rather lovely grey cat. Behind him is an old unsmiling woman, played by Freda Bamford, who is sharpening a carving knife, very slowly and with great care. She is the first really intriguing person to appear so far. A rather sinister conversation about birds being killed and rabbits caught in traps ensues before we cut back to the urban 1970s kitchen, in which Michael and Jill are eating an evening meal. Jill announces she might take the poster down and suggests that the figure could be a boy in drag. I became quite distracted by the absurdity of the husband’s tie. The wife has a way of talking that is very annoying. She points out that if you look carefully at the picture you can see a tattoo on the figure’s arm. In the background, classical music plays - I think this may be intended to suggest effeteness.

The telephone rings and the husband answers, and then hangs up, saying it is a wrong number. Then it rings again and he says he will take it in the study. An illicit conversation ensues. He asks about the caller’s tattoo and whether others know about it and whether it is a popular thing in their line of work. He accepts that, obviously, all clients would see it.

The husband then lies, saying it was friends asking them to dinner. While he’s been out of the room, the wife has inked in the tattoo on the arm. A discussion ensues about the rarity of sex between them. The husband then says he is going to head off and try to find the caravan in the photograph. On and on it goes. We see him in the car, in the country, listening to dissonant modern classical music. He picks up a hitchhiker. Back at headquarters, someone with a gold bracelet and feminine fingernails puts jam on toast while listening to non-classical radio and then answers the telephone, immediately putting down the receiver so that we see on the person’s forearm the same tattoo we saw on the arm of the person with whom the husband was in bed.

The hitchhiker is a Glenda Jackson lookalike. We see some slightly flirtatious chat between her and Michael. Back at home, Jill has a cup of tea with Fred, presumably a colleague, who has taken her to a movie because he thought she seemed a bit low. She explains to Fred that Michael is an artist and his creation is himself - and that he wants her to commit suicide. She shows Fred some pills that are prescribed to Michael that she believes he wants her to use to kill herself. Fred throws them down the lavatory. Michael meanwhile discovers he isn’t as charismatic as he had imagined, as Glenda Jackson goes off with someone her own age. He is then accosted by an evangelical, to whom he shows the photograph. The man is able to tell him where the caravan in the photograph can be found.

Back at the house, Jill and Fred are woken from sleep (in the same bed) by the telephone. It's Michael. He says he’s found nothing and might come home at the weekend. Jill expresses consternation as she was planning to join him.

The following morning Michael finds the caravan, knocks on the door and is met by the knife sharpener, who once again lights things up quite a lot by her mere presence on the screen. When Michael shows her the photograph she suggests he go to the local police. He notices an alabaster heart, which he recognises as his. She tells him to come back tomorrow. He leaves and we realise David Cassidy has been watching the exchange. He comes into the caravan to find the knife sharpener burning the photograph over the sink. “I promised to make inquiries in the village” she says, laughing.

Back at the house, Michael is greeted with enormous relief by Jill. She is full of concern when she hears that he is going back the next day. She tries to persuade him not to, but he ignores her. She says she was testing him. She pretends she sent the photograph just to make mischief, but he doesn’t believe her. She confesses she went to bed with Fred. “Good”, says Michael, “good for Fred.” “Don’t you care”, she asks. He says he will try to but admits he’s not been much use sexually later. She suspects him of wanting Fred to take her off his hands.

He changes the subject, asking her about the alabaster heart he bought for her in Positano, which has now vanished from the house. She asks him to just tell her the truth. “It’s a very neurotic symptom, love, always wanting to be told the truth”, he replies.

The next day he is greeted by the knife sharpener, who has prepared “a good spread” for him. She offers him “country wine”. “Home-made that is”, she says admonshing him to “drink it down”, explaining that it will “do you good”. She is drinking none, but she says it’s special, for guests. “Drink it down”, she says “and I’ll wash the glass and we’ll have the tea”. She tells him the girls in the photograph were bad girls and that they are dead. Back at the house, Jill records a new answerphone message and then leaves. In the caravan, the knife sharpener asks whether Michael makes anything. He boasts about his programmes and articles about the arts, but she says that’s not making things, but merely talk, air. He says he doesn’t think helping people appreciate the arts is nothing, as a lot of people in the city lead a very dead kind of life nowadays and giving meaning helps them. She says presumably when people come asking for his views, he gets paid. He replies that people don’t come asking; they need to be told. This is my favourite moment in the entire play.

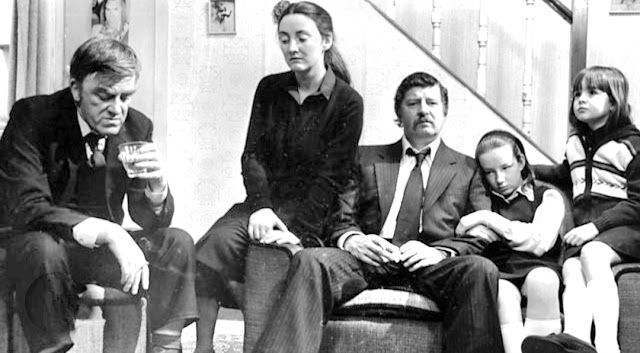

At precisely this moment, as the knife sharpener explains that she draws social security - more precisely supplementary benefit - and that her daughter is a teacher and it’s very difficult to raise a family in a caravan, the country wine begins to take effect. “Take a sandwich” urges the knife sharpener, assuring the husband that they are made of paste that is 80 per cent salmon, Michael realises he cannot move. The knife sharpener tells him what the wine is made of. We see Jill dashing through narrow lanes in a small car. Back at the caravan, David Cassidy and the knife sharpener tuck into the paste sandwiches. The knife sharpener reminds him he must save some for “our girl”, who arrives shortly afterwards. She turns out, of course, to be Jill, and when the knife sharpener asks, “Is that him” she answers “That’s him”. He can hear what you say she is told but she says she’s already said too much. The sharpener asks if she wishes to deal with him but she prefers that “our boy” tends to it. There is almost a reprieve for the husband when the evangelical knocks on the door, with his usual message that selfishness causes everything bad. He is fobbed off, and, shortly after, the meaning of the initial scene, (the one I forgot about all through the play), becomes clear. In the final scene, we see Jill listening to a talk by Michael called Imagery and the Archetype being broadcast on the radio. It is about how inside each modern human despised morlocks grow and become more powerful and in the end we will be smashed and eaten by them.

The play ends with titles running against a background of the one thing that holds this nonsense together - the knife sharpener, singing along to an old folk song being broadcast on the radio.

Comments

Post a Comment