Hearts and Flowers by Peter Nicholls, first broadcast 3 December, 1970

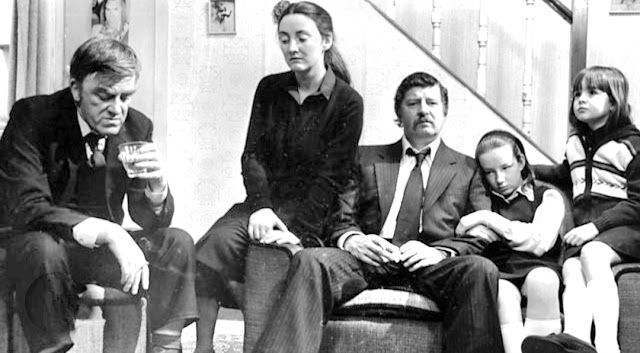

Apparently this is what he looked like in the early scenes

It may not be worthwhile writing about this play, given that the only version I could find is so exceptionally dark and blurry that you might as well be listening to a radio play as watching a television play. All the same, as I was an eccentric child who often feigned illness in order to stay home from primary school to listen to the Afternoon Play on the BBC, I enjoyed it.

The play opens with the camera trained on a bed in which you eventually realise a woman is already lying and, while you watch, or listen, her husband joins her. There is a conversation about sex and whether she is still interested in him. She appears not to be enormously, and she mentions that she may be pregnant. Then the telephone rings and the husband is called away to his mother's, where, it transpires, his father has dropped down dead. A doctor turns up and either that night or the next day an undertaker. Everyone is highly matter-of-fact. With surprising efficiency a funeral is arranged, the man's older brother arrives from London, where he is a television celebrity, a cast of friends and relations are gathered, a faintly comic funeral is conducted, overseen by a vicar who reminded me of AN Wilson at his most old-fashioned.

The rest of the play is taken up with the wake back at the mother's house, including an interlude in the upstairs room where the husband character grew up, sharing with his older brother, who is the minor television celebrity of today.

Around now, the picture quality suddenly improves and it emerges that the husband from the first scene is a very young Anthony Hopkins, his wife a poor man's Mrs Good from The Good Life and the actor playing the television celebrity an actor who is vaguely familiar.

The conversation downstairs over the funeral baked meats is amusing and each character is wondefully brought to life. Upstairs we discover that the wife as a very young woman had an affair with the television celebrity older brother, presumably unbeknownst to the man who is now her husband.

The contrast between the older brother, a romantic, full of nostalgia, and the younger brother, an urban planner/architect, is the crux of the play. They disagree on most things. Whether this is because they are the archetypes of modern British man, 1972, or whether because they are, either knowingly or not, rivals for the Hopkins character's wife, I cannot say. Hopkins would like to pull down the church in which the funeral takes place and is full of a desire to deconstruct Britain's class system. It is odd that he is actually the man of the future, while his brother, the man of television, the medium of the future, is more attached to the status quo. Yet it is he who articulates sorrow at his father's death and the consequent passing of an era, looking around at the not obviously exciting bedroom furniture and saying, "All these redolent chairs and tables, the landscape of our childhood" and proclaiming of the dead patriarch, "He wass a good man who lacked our advantages, the advantages he gave us".

"You could do a super piece on him in your next programme", his brother replies.

"What’s wrong with showing a bit of feeling?" asks the television celebrity and Hopkins answers:

"Nothing. For you it’s a good living. I just think there are more pressing matters and nostalgia is enervating and in Britain almost a disease."

"And what are 'more pressing matters'?" asks the older brother

"Sewage disposal, noise abatement, traffic control, clean air, population, all good for a belly laugh on your TV show", says Hopkins.

"You haven’t been watching", protests his older brother, "Half my programme last Saturday was given over to the problems of air pollution," to which Hopkins scornfully, if not entirely accurately, (diesel?) responds, "Yes and then you fly off to New York in a trail of diesel and supersonic bangs."

Quite amusingly the older brother asks, "How do you expect me to go? By rowing boat?"

It's intriguing to realise that even 50 years ago people were using pollution to beat each other around the head. If offered the alternative of an evening with Mr Sewage Control or Mr Landscape of Our Childhood, I would be hard pressed to choose between them. If these were genuinely the two main types of human being rising up to take charge of Britain in 1970, I begin understand why the nation's governance is in the mess it is today.

Despite the quality of the picture, I really enjoyed this play, especially the part where the cups of tea and pieces of cake are being handed around downstairs. The characters are almost in the realm of pantomime, which is not a criticism, particularly as a very fine balance prevents them from being fully panto - and this partly because the performances are all superb. The first half is extremely murky visually though, so I suppose you would have to be steadfast to sit it out.

Comments

Post a Comment