The Right Prospectus by John Osborne, 1970

Zoë - The Right Prospectus is the second play to be broadcast in the Play for Today series. Together with its predecessor, The Long Distance Piano Player, it ought to have been enough to have the entire series cancelled, in my opinion. I have rarely seen such a tedious load of piffle.

The play opens on the visit of a wealthy couple to a boys' public school. The usual cliches associated with the portrayal of such institutions - a cricket match on a sunlit pitch overlooked by fine buildings, boys in tail-coats, others in boaters, a headmaster in a woodlined study, are all in evidence.

The visit complete, the couple drive off in a Bentley or similarly grand vehicle, complete with chauffeur. We find them next at lunch in a country hotel or restaurant, where they pore over prospectuses for further public schools. It emerges from their conversation that they have no children and that the wife wants none. Having removed the broad brimmed green hat she wore to tour the school - it matched her natty green skirt suit and high heeled shoes - she muses on the peculiarity of messing up one's life with infants. She has a face that might be described as mildly elfin, framed by short hair.

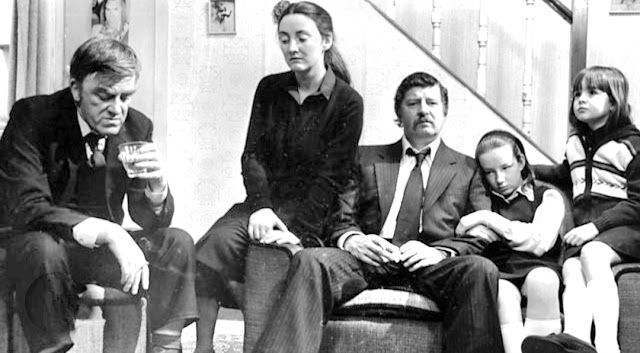

Her husband, it becomes apparent, (even through the blur of a very poor quality bit of video), is the actor who will one day become Arthur Daley. For now he is a chap who, judging by a remark by the headmaster in the first scenes, has achieved some kind of public recognition and, judging by his means of transport, has acquired some kind of economic security. He clearly is dotty about his wife and perhaps for this reason is going along, pretty reluctantly, with a scheme that she describes as, "the best idea we've ever had."

At last the wife lights upon a prospectus for a school that she declares will be perfect. For what, we may wonder, if there are to be no children from this marriage? The action moves to another headmaster's office and a meeting that ends in agreement between all parties. This agreement, it turns out, concerns the couple becoming pupils at the school.

The two of them are quickly assigned to different houses - all very Harry Potter, although without the sorting hat. The wife either gets the better house or is simply better at fitting in. Anyway, she thrives and wins prizes across the board, from her sporting activity (she beats all the boys at tennis, somehow, which seems unlikely, but then nothing about this story is likely really) to academic work. Arthur Daley meanwhile does not thrive. He is monstered by the head boy of his house, who spouts much wordy nonsense. He endures various unpleasant boarding school meals, humiliations by masters and a muddy cross-country run. Then the couple reunite and are driven away in their swank car.

The grand public school looms large in the English imagination. I assume John Osborne, the author of this play, intended to produce a critique of such establishments - Arthur Daley declares at one point " You come to these places to do things you will never want to do after you have left." Perhaps Osborne also had the creation of some kind of metaphor in mind. The wife's enjoyment of school life and her success within its confines may indicate that feminism has led to women taking over and excelling in what was once a world designed for and shaped by males, or that boys' public schools are ideal for effeminates.

Who knows. One character declares "Sociology's the only real science because it's art and it's also political." Perhaps that's the problem - Osborne believes sociology is art; I don't and similarly I can see no real art in this piece.

Phil - It must have seemed a real coup when John Osborne agreed to write a television play for the BBC's new Play for Today series. With Look Back in Anger still fresh in the public consciousness, Osborne was in the top tier of British playwrights and I'm sure that many television sets in North London were tuned to BBC1 on October 22nd, 1970. However, like its predcessor, The Long Distance Piano Player, I found the play as riveting as a Human Resources seminar and only managed to watch the whole thing by having a long break in the middle.

The Right Prospectus felt like a satire that had completely missed its target and the humour seemed limp and lifeless because it was based on a completely implausible premise that didn't even work as an allegory. A childless marriage couple in early middle age become pupils at a boys public school. One of them thrives while the other hates it. Is that it?

Perhaps I am too shallow to appreciate Osborne's observations. In a very interesting and detailed blogpost by John Hill about The Right Prospectus (which I lazily pinched a few images from), the author gives a glowing review:

Perhaps I am too shallow to appreciate Osborne's observations. In a very interesting and detailed blogpost by John Hill about The Right Prospectus (which I lazily pinched a few images from), the author gives a glowing review:

"The Right Prospectus remains one of the most baffling yet

beautifully realised and captivating plays ever produced for television.

W. Stephen Gilbert is probably not exaggerating when he calls it

‘possibly the best thing Osborne ever wrote, and certainly the finest

thing he wrote outside of the theatre."

According to John Hill's excellent article, the play was a critical success, although at least one reviewer admitted that they were baffled by it, so what are Zoe and I missing?

I am a big fan of George Cole, from his wonderful cameos as 'Flash Harry' in the St Trinian's films to his masterly performance as Arthur Daley (surely a grown-up Flash in all but name?), so my expectations were high, but he failed to convince me that he was a real person. Both Cole and his screen wife, Elvi Hale, came across as characters who weren't likeable enough for the viewer to be rooting for them, but not dislikeable enough to make us care if they succeeded or failed. As for Osborne's use of language, which Hill hails for its confidence, I just found the dialogue mannered and unconvincing.

We were never really given a convincing reason why this unlikely couple wanted to become pupils at a public school, or why the headmaster accepted their application without any prevarication. John Hill writes that the director tried to rein in the more surreal aspects of the play, but the result is a work that is neither fish nor fowl.

Comments

Post a Comment