Kate the Good Neighbour - broadcast 6 March, 1980

Zoë:

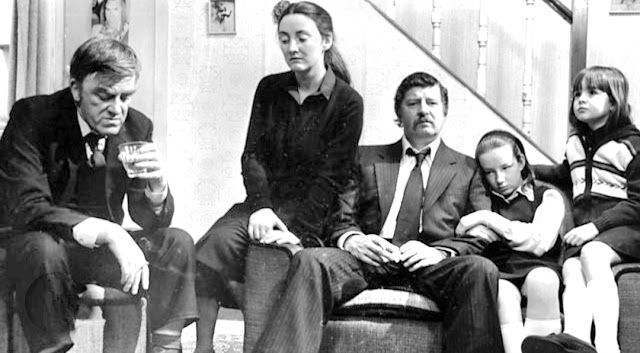

Kate the Good Neighbour opens with a series of vignettes of Kate, a tweed-suited elderly woman, as she goes about her neighbourhood, setting various members of her local community to rights. First, a greengrocer who runs a stall in the local market, (this is not yet the world of big supermarkets), is verbally rapped over the knuckles for trying to flog bad tomatoes. Then Kate goes to “help” a recently widowed woman, played by Dandy Nicholls - unforgettable from her earlier role as Else Garnett, aka “the silly old moo”, (especially memorable for me is the episode where, after the Garnetts have the telephone installed, Else sits quietly in the background, steadily reading her way through what look like rather large volumes - which you realise at last, when she exclaims, “Ooh, you’ll never guess who’s in here", are the newly delivered London telephone directories).

Kate chivvies Dandy Nichols’ character into crushing her foolish sentimentality, (as Kate sees it), and ridding herself of the few mementoes she still has of her husband and their life together. Finally, Kate, looking awfully like Mary Poppins at her fiercest, clears, by force of will, a group of young boys from the alley they have commandeered for skateboarding, insisting they go to the park where there is a track built especially for them to use.

By the end of these scenes, while I felt a certain admiration for Kate’s intransigence, at least when she takes on the young boys, I couldn’t say I had warmed to her. She seemed rigid and quite unable to understand the difficulties of others, intolerant of human weakness and without humour or gentleness. She also reminded me of the legions of women who gave a very similar impression almost everywhere I went in my childhood – teachers, librarians, general do-gooders, as well as Nigel Molesworth’s grandmother, who insists to her grocer that his “gorgonzola isn’t what it used to be” – a surprising complaint in the deprived world of post-war Britain, as is the dialogue between Kate and a household help about the quality of the camembert and brie on offer in a local shop.

After our introduction to Kate via her activities in her neighbourhood, we return home with Kate to a small first-floor flat, where we are allowed to watch and listen to her thoughts as she fills in her diary, a habit her aunt told her in childhood was vital – “A day not recorded is a day wasted”. Kate unscrews the lid of her fountain pen, slides out the blotting paper from the page she filled in the day before and begins to write.

Thus we learn what is going on in her mind. As it happens, she admits, autumn, the time of year at which the play opens, is always a season when she finds herself prone to what she calls “fancies”. What these are in fact is regrets. She tries to drive them away by practising piano and performing good works, but it is useless. She takes down her diary from 1941 and, through it, a clearer understanding of how Kate became the tightly-wound, driven woman we see in the present day unfolds.

I don’t want to give away the plot so I will not explain the events that develop. Although there is a happy ending of sorts, the story is really a tragedy – Kate, orphaned in the first war, brought up by an aunt who told her she was plain and led her to hope for nothing from life, is unable to trust good fortune when it comes her way and makes an immensely sad error that leaves her shut up within herself, trying to ignore a great deal of regret.

As in the second play that Phil and I looked at, a consciousness of the war permeates Kate the Good Neighbour. The way of life portrayed on the screen, with all its deprivations and smallness, seems still to be steeped in the memory of the conflict, even though the play was broadcast 35 years after war’s end. While things, such as sharing bathrooms and unmodernised living quarters, are shown to be changing, that change is happening very slowly. Life lacks many of the material delights we now take for granted – for instance, there is no sign of a decent cup of coffee anywhere in the whole one-and-a-half hours of the play’s duration.

As a child, I would have said, “Hurray” if you’d told me such women as Kate were a vanishing breed, but the genius of Kate, the Good Neighbour is that I now feel empathy for them and wonder whether their passing is entirely a good thing. Leaving aside the humanity revealed by the playwright in his character, the certainty and the sense of right and wrong that these women displayed, which once struck me as intransigent, might now be rather refreshing to witness. As well as being bossy and bloody-minded, this excellent play helped me realise that they were courageous and steadfast in their own way. Such women were a force to be reckoned with once upon a time and their no-nonsense approach, while often insensitive, might today be an antidote to certain stupid things.

The success of Kate the Good Neighbour is partly due to Peter Ransley’s excellent script, which never disguises the fact that Kate is abrasive but also succeeds in revealing her humanity, evoking the audience’s sympathy for a misguided and consequently very lonely soul. Additionally, Ransley is extremely well-served by the acting, which, with one exception, is superb. Rachel Kempson as present day Kate is especially impressive, but I am also surprised that the actor who plays a young airman seems not to have gone on to a further career, nor the young man who plays a very good-looking social welfare officer.

The play itself has absolutely no axe to grind about any issue. Instead it attempts to portray a single, easily misunderstood character in all her complexity. For me at least, it succeeds brilliantly, providing, as I have said, a new insight into and sympathy for the many indomitable but prickly old ladies that marched about the streets of my childhood. How many of them, like Kate, experienced happiness briefly and then had it snatched from them, whether by the exigencies of war or, as in Kate’s case, because they impulsively stole it from themselves and now are afraid to even remember what they lost? Too many, I fear. The poignance of their situation is beautifully exposed.

I am so grateful to Phil for suggesting Kate the Good Neighbour and, if the IMDB website is right in the claim that Ransley wrote two other Plays for Today, I will look forward to them enormously. Kate the Good Neighbour is not jolly or funny, which, coward that I am, means I wouldn’t probably have gone out of my way to watch it. I am so glad I did. It sounds like hyperbole but I think it may be a genuine masterpiece.

| ||

To the rest of the world, Kate is, at best, an aburdity. At worst, she is a positive nuisance. As a young woman she lodged in a large Victorian house and 40 years on, still occupies the same rooms, but all the other tenants are long gone. In the evenings, she records her small victories in her diary. It is at this point that the comic leans towards the tragic, as we see a lonely woman trying to find some meaning in her life.

This ordered way of living might have continued for years, but two events happen that prompt a crisis, forcing Kate to look back to a pivotal moment in her past when she could have followed a very different path. I'm not always a fan of flashbacks, but in this play they work very well. The young Kate is ably played by Sherrie Hewson - of Coronation Street and Loose Women fame - and although her accent isn't always as cut glass as Rachel Kempson's, she is pretty convincing.

The greatness of this play lies in the way that it takes us behind the masks that people wear to face the world, showing us the disappointments and vulnerabilities that have forced them to develop a brittle outer shell. A lesser writer might have enjoyed mocking Kate and everything she stands for, but Peter Ransley treats her with compassion and respect. Two apposite quotes spring to mind: "Life is basically tragic, with comic overtones" and "To understand all is to forgive all."

Central to the success of Kate, the Good Neighbour is Rachel Kempson's excellent performance. Her real-life role as the wife of Sir Michael Redgrave and mother of Vanessa, Corin and Lynn seems to have eclipsed her work as an actress, which is a great pity. Although she has a great script to work with, it is Kempson's ability to imbue every small look and gesture with meaning that makes her acting so convincing.

As viewers, we not only see the contrast between a young and old Kate, but also the huge change that has taken place in society. Kate can longer rely on being greeted with the deference that her class once guaranteed and without wishing to undermine Zoë's desire to avoid spoilers, I found the ending very poignant.

I'm so glad that Zoë enjoyed Kate, the Good Neighbour. I watched it with no idea what it was about and soon found myself completely absorbed. I'm sure that I would have enjoyed it as a teenager, but watching it at an age when I find myself increasingly occupied by the past, ruminating over the I choices I made in my youth, gave the play an added dimension.

In the very unlikely event that I become a transwoman, I can think of worse personas to adopt than Kate's. I would enjoy waving my umbrella menacingly at ne'er-do-wells and becoming the bane of intransigent local government officers. Self-appointed busybodies like Kate may be a nuisance, but to recall another famous quote, "The only thing necessary for evil to triumph in the world is for good men (and women) to do nothing." Thank God for all the Kates.

Comments

Post a Comment