Under the Hammer by Stephen Fagan, broadcast 1984

I loved this play. It is set in a very superior English auction house as a pre-sale paintings exhibition is being readied for public view. The credits roll to the sound of an auctioneer calmly accepting bids in the hundreds of thousands. This soundtrack fades as the opening scene is revealed - porters in dust coats setting up partitions and hanging pictures, while suave, suited men stroll about, discreetly overseeing things.

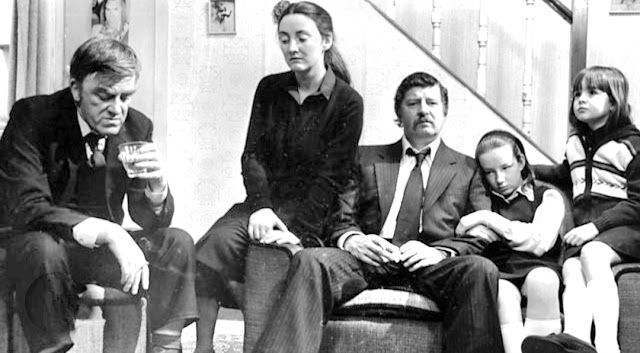

Peter Vaughan, the man who is clearly the senior porter climbs down from a step ladder and announces it is time for a tea break. All the porters down tools and we head with them below stairs. Peter Vaughan's character, Les Stone, acts as mother, pouring milk into everyone's mugs of tea and handing them around. After a discussion about the technicalities of lighting and the unreliability of the electricians with whom the porters work, Les reveals that the Princess of Wales will be visiting tomorrow. This news is received with excitement by almost all the members of the team. However one, it emerges, sympathises with Russian Communism and affects not to give a toss.

Meanwhile, out on the street, we see a natty gent in bowler and three-piece suit, carrying an umbrella and briefcase, emerge from a taxi, with the help of a white-gloved doorman. This is the head of the auction house, John Bourke-White, played by Michael Aldridge. His performance captures the combination of extreme politeness and utter lack of warmth that characterised - or possibly still characterises - a certain kind of drawling upper-middle-class public school old boy. His offsider, Geoffrey Anderson, played by James Maxwell, is equally good in a similar role. Geoffrey pretends he cares slightly more about those beneath him in the hierarchy but when he gets Les's name wrong at one point it becomes clear his empathy does not go very deep.

All seems well until a tall man dressed in an impeccable off-white suit and matching shoes, (exceptionally neat but nevertheless clothing no true English gent would be seen dead in), enters the gallery and stands in front of one painting for quite a long time. He then goes to reception and asks to have a word with John Bourke-White. Nina Botting as the receptionist is superb in this scene, exuding with only her accent her conviction that she is superior to any American, even one who is the scion of a big Manhattan art house.

The young man is shown into Bourke-White's office and after pleasantries he suggests that a Van Gogh being sold by the Russian government in the auction may not be genuine. Bourke-White says little - (although he does in passing endear himself to me by admitting he doesn't worship at the feet of Vincent Van Gogh) - but adjourns with the American to the gallery floor, joined by Geoffrey Anderson. Much smooth talking about provenance and sales made in Germany during the war ensues. The porters are asked to take the picture downstairs to be examined more closely.

Les is assigned to take the painting to the examination room and in the process, in an argument with his Communist colleague, kicks the painting, making a visible hole. Geoffrey and Les then accompany the painting to Trevor Boveen, a raffish restorer played by Peter Bayliss, who agrees to spend all night repairing the damage Les has caused, readying the picture for display the following morning.

Les stays with Trevor all night. Geoffrey Anderson and John Bourke-White drop in, wearing dinner jackets, on their way home from their evenings out. Boveen clearly despises the airs and graces of the gallerists, as I suppose they would now be called, although he is no better than them in the way he orders Les about.

Bourke-White finds the experience of visiting Boveen almost insupportable - "the smell", he exclaims to Geoffrey in the taxi afterwards. He goes on to tell Geoffrey that Les will have to be let go, that you can't trust a man who kicks a painting, even if he has taken care not to do so for twelve years beforehand - it's like a dog who bites, he contends: once they've done it a single time, you can never trust them again. Geoffrey demurs rather feebly but in the end agrees to give Les his marching orders in the morning. The next day Les is scheduled for a ten-minute slot with Geoffrey. Loyally, he agrees that he deserves his fate and decides to go immediately, without fanfare, rather than waiting until after the visit of the Princess of Wales.

Les goes downstairs and, as he is packing up to leave, a keen young porter called Billy, unaware his senior is being "let go", appeals to him about being allowed to wear the brand-new suit he has bought for the occasion of the Princess of Wales's visit. Les, still sticking by the rules of the system that is dumping him, tells Billy that wearing his suit rather than a dust coat is out of the question, even though Billy has spent cash he can't afford on his new clothes.

The Princess of Wales arrives. Les lumbers off, accepting his fate and the system to the last - never, it seems questioning the fact that the seniors, while happy to punish him for a momentary slip-up, have no compunction about selling a painting that may be a fake and, if it isn't, is of dubious provenance and now has a hastily mended flaw. The credits roll once again to the sound of huge sums of money being bid for what we now know may very well be worthless or highly compromised objects.

I don't know what Stephen Fagan, the author of the play, intended with Under the Hammer. I suspect his sympathies may well have lain with the Communist porter and the play may be an indictment of the English class system. If it were only that, it would be a bore, but actually it is wonderful fun, mainly thanks to its superb performances, especially from Vaughan, Aldridge, Maxwell and Bayliss. The last three are brilliantly observed and very funny. Vaughan meanwhile is touching, a figure who has dedicated himself to a system he does not question. Most of his performance is not conveyed through words but through expression and movements and, in what is essentially a light entertainment, he manages to create a small tragedy out of his role. In the final shot we are shown of him, we see him from behind, walking away from the auction house for the last time. There is the weary nobility of a beast of burden about the way he moves.

In kicking the Van Gogh, of course, Les has committed what to Bourke-White and his ilk is the worst of all possible sins. It is the sin, as it happens, that the Princess of Wales was also to stand accused of - a failure of self-control. The auction house bosses, immaculately dressed, ruthless, impeccably well-mannered and totally unscrupulous, care nothing for morality and everything for restraint. This includes restraining themselves from ever examining their real motivation. They can discuss trivialities with languid energy - there's a terrific scene in which Bourke-White muses in some detail about hessian, for example, (I also love the moment when, having inquired about the American visitor's father's health, he cuts him off with an almost admonitory, "Sad, sad, sad" - code, as I took it, for, "I really couldn't care less") - but making money, the driving force behind their balletic charade, must never be mentioned and the amount they care about that - or anything else - must never be revealed.

Incidentally, this Twitter thread suggests that in the matter of greed and lack of principles the art world hasn't changed much since Under the Hammer was broadcast.

Phil - There isn't much that I can add to this comprehensive and perceptive review. I agreed with it all and particularly liked the description of "the weary nobility of a beast of burden" for poor Les. I would love to know what Steven Fagan's agenda was when he wrote the play and now I've discovered that he was recently - and perhaps still is - living a few miles away, I'm tempted to knock on his door and ask him.

On the surface, Under the Hammer is a satire on the art world and the way its terribly civilised veneer conceals what is, at heart, a cut-throat business with occasionally questionable practices. However, an equally important aspect of the play is its examination of the class divide. Like the 1970s drama Upstairs Downstairs, we see the auction house from the perspective of both the masters and the servants. In the hands of a lesser writer, it could have been a crude device to make predictable points about the injustices of the class system, but Fagan observes the "show, don't tell" rule of writing and avoids preaching to his audience.

I also wonder if the more light-handed approach to the subject of class reflected the sea change that took place in the early 80s, after the famous Winter of Discontent had brought Margaret Thatcher to power. But perhaps auction houses were never hotbeds of class war.

The atmopshere of Under the Hammer is very different from the often grim polemics of ten years earlier. We are in Thatcher's Britain and although there is still one final epic battle to come, in the shape of the Moners' Strike, the class war seems largely over. Dagenham Man - that mythical creature favoured by the pollsters - is far more interested in buying his own council house than joining a picket line.

This social change was, perhaps, a factor in the imminent demise of Play for Today, which felt like a relic of the 1970s. However, in hindsight, the series never really went away. It just resurfaced as the slicker Screen Two, reflecting the more affluent society of the mid-80s. In terms of production budgets, Screen Two was a yuppie cappucino to Play for Today's own-brand instant coffee.

But I digress. To return to the subject of this post, I really enjoyed Under the Hammer. It was entertaining, witty and quietly subversive, with a superb cast. I would warmly recommend it.

On the surface, Under the Hammer is a satire on the art world and the way its terribly civilised veneer conceals what is, at heart, a cut-throat business with occasionally questionable practices. However, an equally important aspect of the play is its examination of the class divide. Like the 1970s drama Upstairs Downstairs, we see the auction house from the perspective of both the masters and the servants. In the hands of a lesser writer, it could have been a crude device to make predictable points about the injustices of the class system, but Fagan observes the "show, don't tell" rule of writing and avoids preaching to his audience.

I also wonder if the more light-handed approach to the subject of class reflected the sea change that took place in the early 80s, after the famous Winter of Discontent had brought Margaret Thatcher to power. But perhaps auction houses were never hotbeds of class war.

The atmopshere of Under the Hammer is very different from the often grim polemics of ten years earlier. We are in Thatcher's Britain and although there is still one final epic battle to come, in the shape of the Moners' Strike, the class war seems largely over. Dagenham Man - that mythical creature favoured by the pollsters - is far more interested in buying his own council house than joining a picket line.

This social change was, perhaps, a factor in the imminent demise of Play for Today, which felt like a relic of the 1970s. However, in hindsight, the series never really went away. It just resurfaced as the slicker Screen Two, reflecting the more affluent society of the mid-80s. In terms of production budgets, Screen Two was a yuppie cappucino to Play for Today's own-brand instant coffee.

But I digress. To return to the subject of this post, I really enjoyed Under the Hammer. It was entertaining, witty and quietly subversive, with a superb cast. I would warmly recommend it.

Comments

Post a Comment